Would you believe me if I told you that people can be happy doing work they hate?

Everyone wants to be happy. Well, there is actually some debate about what people want and whether the word “happy” is the the most accurate. Call it utility, or fulfillment, or flow, or bliss, or the good life, or anything else you like. I’m going to use the word ‘happy’ to describe an existence that maximizes those moments when you feel proud and thrilled to be alive, and minimizes those where you feel the opposite. Just give me some definitional generosity, or substitute your preferred word that defines what it is you seek.

Now, most people also think that they want to do work that they love. That is, they want the way in which they procure the resources needed for survival and material pleasure to be an activity that is inherently interesting and fulfilling. They do not merely want the hunt to be done for the meat, but they want to enjoy it for its own pleasures. At least that’s what they’ll tell you.

You might be lying

I think a great many people are lying to themselves and others about what they actually want. A lot of people want to be the type of person who seeks meaning in their work, but they actually care a lot more about just finding a way to get the resources needed to relax more. Doing work you love is harder than doing work you can tolerate. I don’t think that’s a bad thing. There is nothing morally superior or inherently noble about wanting to do work that you love, and there is nothing bad about wanting to just get the money you need to work as little as possible. These are personal preferences, and either approach can lead to a happy life. Of course, lack of self-knowledge or dishonesty with oneself about which approach you prefer can lead to unhappiness just as easily.

In other words, doing work you love is not the secret ingredient needed to be happy. At least not for everyone.

There are people who can never be happy unless they are doing work they love. For them, it doesn’t even matter if they make a lot of money at it. If those people chase money and status over fulfilling work, they’ll be miserable.

There are also people who can never be happy unless they have a large amount of money, free time, leisure, and a minimum of stress. For them, it doesn’t even matter much what kind of work they do, as long as it yields them enough money in a small enough amount of time to do what they really love. If those people chase a meaningful career with all the material and time sacrifices that requires, they’ll be miserable.

Who are you?

The key to happiness is to discover which type of person you are, be honest with yourself and others about what you find, and have the courage to live it.

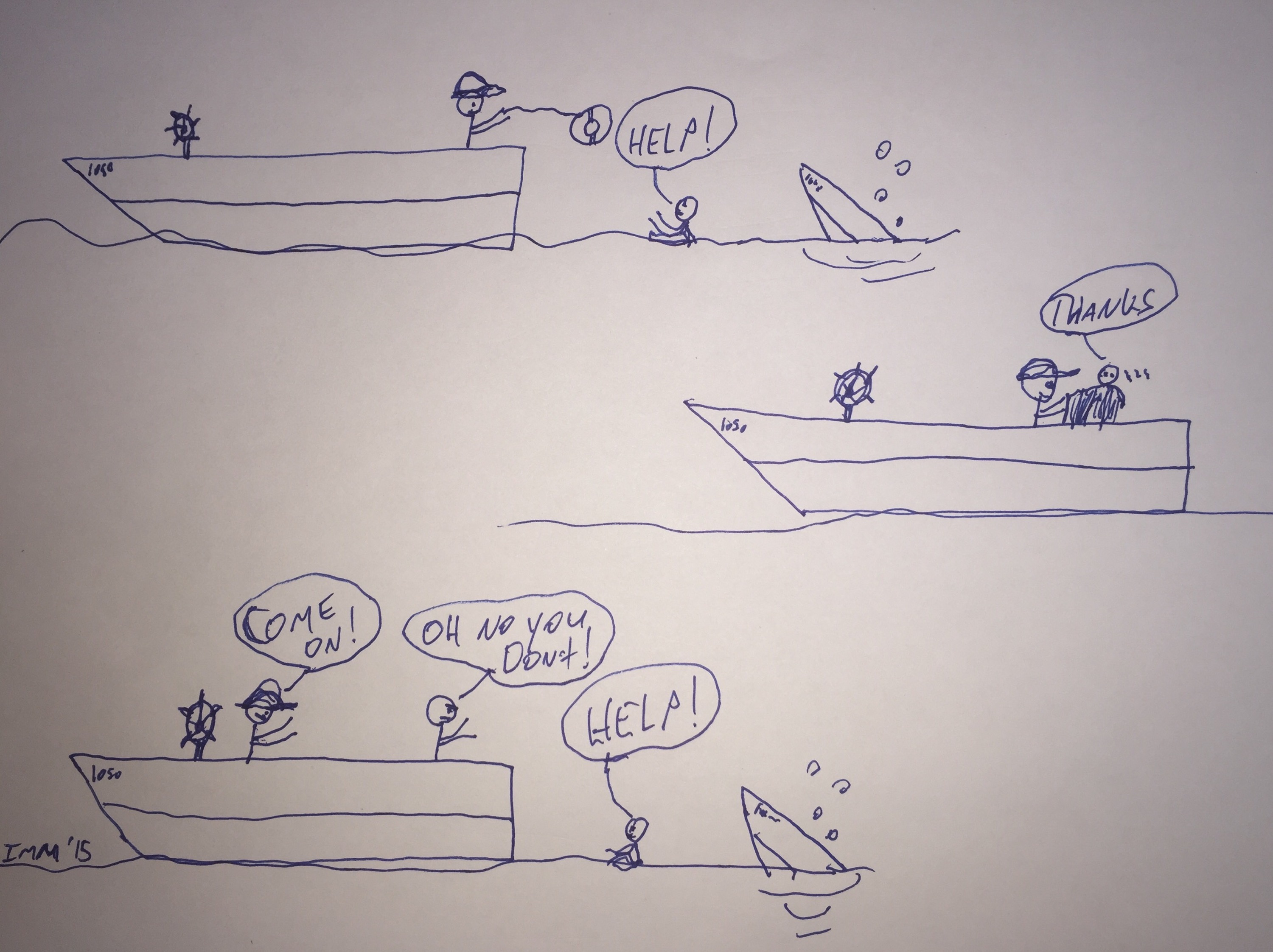

Let me illustrate this with a matrix. I love a good 2×2 matrix. It’s been awhile since the last one I made (in what is still one of my favorite posts), so I decided to conjure up a new one. My graphic design skills are once again on full display. You’re welcome for the visual feast.

Let’s walk through each of the four quadrants one by one. See if you can recognize people in your life who fit them.

Oh, and notice in particular the fact that the amount of money earned is not the relevant factor in any of the quadrants. You can have rich, poor, or anything in between in any of them.

“I love my work and I’m happy”

The upper left quadrant represents those people who have gone all-in to find work that makes them feel alive every day. They may be billionaire tech company founders who live and breath their company, or penniless beach bums who spend all day on the waves and scrape together just enough money giving lessons for a burger and a brew. I know people so passionately obsessed with their work that they’d rather be doing it than anything else. Depending upon what that work is, they may be very wealthy or very poor. They don’t much care. They care about their craft, and so long as they’re doing it, life is good.

“I hate my work and I’m happy”

The upper right quadrant is where people who have accepted the fact that work is not for them hang out. They’ve also come to grips with the fact that the things they actually do love require a good bit of money and time, and work is required to get it. They configure their lives to do the minimum amount of drudgery to get the maximum payoff. I know business owners who have no interest in their industry, or salespeople who would just as unhappily sell something totally different. They just found a niche where they can get what they need.

They sometimes live the Four Hour Workweek life, and truly put in almost no time to keep the income stream going. Those with a longer time horizon and ability to defer gratification may put in a lot more hours upfront and endure a high degree of boredom for the payoff of evenings, weekends, or retirement. I know people who I don’t think would ever find happiness in any kind of work. They want leisure. But they’ve made their peace with this fact and put all their energy into being true to that reality, instead of unhappily chasing an illusive form of work they’d love, or feeling guilty for their material desires.

“I love my work and I’m unhappy”

Ah yes, the martyr. The people in the lower left quadrant are probably the hardest for me to be around. They self-righteously remind everyone about how they opted not to “sell-out”, but then never stop bitching about the costs they incurred for doing so. The truth is, these are people who would be happier seeking money instead of work they think the world will see as meaningful. This is the jazz artist who gets angry every time the Grammy’s come along and some blonde pop star takes home the hardware. This is the adjunct professor who chose an obscure academic discipline with almost no chance of good money but never stops yelling about the injustice in the fact that no one values what they do enough to pay them big bucks.

The funny thing is, this is a phenomenon found almost exclusively in rich countries. The unhappy work purists are typically quite wealthy by world standards, but they can never stop comparing themselves to the richest of the rich. This obsessive tendency to compare reveals their true preference for material wealth over career fulfillment. They’d be a lot happier if they were simply honest with themselves and, as my friend Jason Brennan suggests, got a job at Gieco.

“I hate my work and I’m unhappy”

Opposite of the previous category, those in the lower right quadrant believe themselves to be made happiest by money, status, and “normalcy”. But they are wrong about their true desires. These people chose the best school, the best major, the best internship, and the job with the best title at the consulting firm because everyone around them egged them on the whole way. Surely a great job, nice house, respectable resume, and good income will lead to happiness, right? In their case, wrong.

They find themselves hating their work and not really enjoying the material benefits it brings either. Their weekends are just as dull as the workweek. As they keep ratcheting up the career ladder they also ratchet up their lifestyle, hoping that the next level and a new car will bring happiness. It doesn’t. But because their material quality of life escalates with their income, they feel trapped. If they happen to realize that they never cared much for money and status as much as meaning in their work, it seems too late. How could they give up $180,000 a year to start a band or become a chef? They might lose their marriage, and surely their social standing.

Knowledge and Honesty

Again, every quadrant has examples of both rich and poor within it. The two happy categories include rich and poor as well as those who love their work and those who hate it. The key is not finding the one true path that works for everyone. The key is finding out who you really are. Then not being ashamed of what you find and not lying to yourself about it.

Self-knowledge and self-honesty.

Finally, after discovering and being truthful about what makes you happy, go do it. It’s worth all the costs.

————————————

For more on this topic check out the podcast episode with TK Coleman, “Should You Follow Your Passion or Not?“

Like this:

Like Loading...