Buy this essay in book form on Amazon.

Launching a company is more like having a baby than anything else I can compare it to.

When I had the idea, it was like being pregnant. A weird mix of inevitability and scary hard work. You know this thing is going to – must – come into the world. You also know you’ve got a lot of really tough work to do to ensure you properly nurture and birth it.

These eleven lessons are sort of like a, “What to Expect When You’re Expecting” for startups. These are some of the things I learned from the day the idea for Praxis was conceived, through the newborn and early toddler years.

Today, we’re somewhere in the awkward early teen phase. The lessons I’m learning now are very different, and I don’t yet see them clearly enough to describe them. Babies and teens are alike only in genetic material. Everything else changes.

I don’t share these lessons as a guide to success. I’ve got no idea what you’ll need to do to succeed. Nor do I share them as a retrospective on my own success. We haven’t had a billion dollar exit, or raised tens of millions from celebrity investors, or become a household name. We’re a young, growing company, but we’re still striving every day to become a cliche and Change The World.

This is a look at the founding of the company and the key lessons I learned. I don’t even know if they’re the right takeaways, but they’re the ones that stuck with me.

I can’t tell you what it takes to get to the mountaintop because we haven’t gotten there yet. But I can tell you what it took me to get from idea to where we are now.

11 Lessons I Learned From Zero to Launch

“Can’t change the world unless we change ourselves” – Notorious B.I.G. (probably not)

My colleague TK Coleman and I like to joke about this quote from the trailer of what looks like a badly made movie about one of the greatest rappers of all time. It doesn’t seem like Biggy would’ve uttered such an empty cliche, so we use it in situations that get too close to cheesy inspiration as a way to playfully mock self-seriousness and pretension. Never fails.

But like all fluffy cliches, it’s true. That’s the first lesson for getting a company from idea to reality.

Lesson 1: You can’t build a company unless you build yourself

TK was busy building a career in Hollywood, hustling to act, produce, write, and launch a entertainment tech startup. He decided to do something that had nothing to do with his career goals and was not required for any job. He started blogging every single day.

TK prioritizes personal growth over everything. He’s a voracious reader, and he decided he needed to push himself to do more than consume ideas. He needed to create, and ship them out to the world. I watched him transform from an irresponsibly curious guy to a disciplined, creative machine. Then he turned it on me.

He challenged me to blog every day for 6 months. I committed, and that was the first step in the launch of Praxis.

The blogging had nothing to do with startups or Praxis. It had to do with pushing myself to become a better version every day, even if I didn’t have to. I had a great job and daily blogging added nothing to it. But it worked wonders for my personal growth. I became a creative machine.

More ideas came, more energy, more confidence, and more clarity. Finally, an idea a decade in the making came into focus. An alternative to college. It seemed so simple, and I’d been sniffing around the edges of something like it since my own underwhelming university experience. Praxis was born because TK continued to build himself when he didn’t have to, and pushed me to do the same.

We built the company around this culture. Every member of the team is inspiring. They are each committed to relentless personal growth. That’s why it works. A person who knows how to grow themselves and add value to their own life can grow an idea and add value to a company.

I had a lot of entrepreneurial ideas prior to Praxis. Most were pretty weak, some were good. But it didn’t matter. I didn’t have what it takes to execute on any of them until I pushed myself much, much harder on personal growth. Monthly challenges, daily blogging, and a commitment to doing one thing each day to add value to myself were prerequisites to launching a company.

The idea matters. But ideas come and go and are unpredictable. You can’t wait around for a great idea. Get busy building yourself so that if and when a great idea comes, you’ll be ready and able to act.

“In some attempts, it is glorious even to fail.” – Longinus

Everyone is too scared of failure. But also everyone glorifies failure too much. ‘Failure porn’ is a real genre of Medium articles and trendy startup swag. It’s pretty stupid.

Failure sucks. It’s awful. It should be avoided. You shouldn’t feel weird for not liking failure. You should want to win.

But some things are worth failing for. When you find one, you need to act and fast.

Lesson 2: It’s gotta pass the willing to fail test

I had a lot of business ideas prior to Praxis. All of them shared a common trait. They all required several things I didn’t have if I were to pursue them.

“If I knew for sure about X, I could try this.”

“If I had X amount of money, I’d try this.”

“If I could find person X, I’d try this.”

I liked the ideas, but I needed less risk in order to take a step. In other words, I was willing to launch any number of them, but only if I knew there was very little chance of failure.

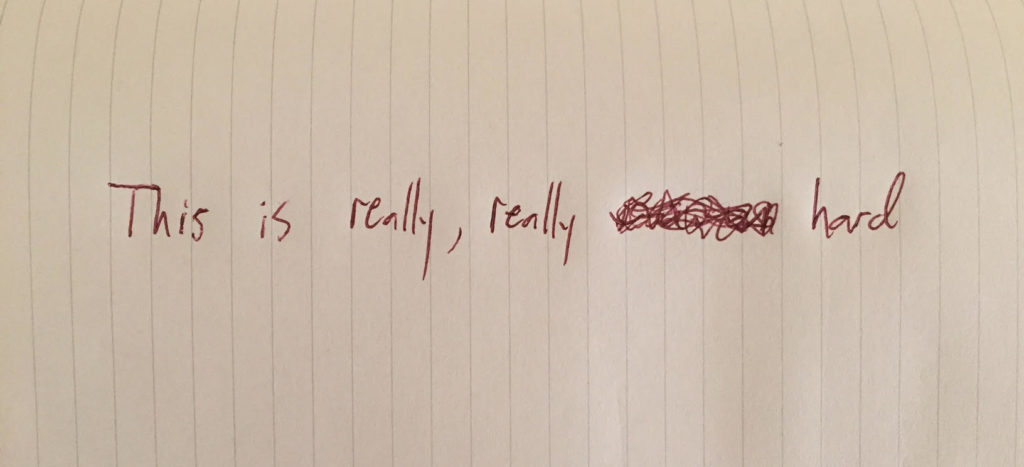

That’s a sign that I’m not the right person to launch that company. If you’re in it because you think it’s a sure thing, you will quit when it gets really, really hard. And it will.

Praxis, on the other hand, was so all-consuming and captivating that none of those objections mattered. I didn’t have money and I didn’t know how to get it. I didn’t have the team, expertise, market knowledge, or any assurance demand was real. I didn’t care though.

I was so obsessed with the question, “Is my theory about a better way to build a career correct?” that I needed and answer more than I needed the answer to be ‘yes’.

This was the first business idea I was willing to fail for. When I thought about trying Praxis and failing, it felt ten times better than the thought of not trying it at all. That was the test. That was how I knew this was the one.

That’s when I cashed in all my chips. I don’t want to fail, but I want my answer more than I want to not fail.

“I would go 0 for 30 before I would go 0 for 9.” — Kobe Bryant

Launching a startup takes some big, scary leaps. You can’t leap tentatively. You can’t go in with an escape plan. You need to burn the ships behind you when you reach the shore in order to have the tenacity necessary for the attack.

Lesson 3: Go all the way or don’t even try

When I knew I wanted nothing more than to get Praxis off the ground, there was one more hurdle before I got started. My most important partner in every endeavor needed to be on board. My wife.

I’m pretty persuasive and she’s pretty trusting of me, so many times in our marriage I talk her into something. She’s not an easy sell, but if I persist enough, I can usually get at least a tepid ‘OK’. The problem with anything less than full-hearted agreement is that if things go south I’ve got to pay later for pushing her further than she really wanted to go.

Even if unspoken, the feeling that I dragged her into something that turned out badly is awful, and a wedge in the family. It puts me in a defensive position, irrationally trying to justify the decision while she goes on the offense and uses her original hesitancy as leverage against me.

I knew that a startup was unlikely to succeed under these conditions, and my family certainly wouldn’t. That wasn’t an option. I needed her in on this 100% if I was going to be able to go in 100%.

So I made a pitch. It might have been the weakest pitch I’ve ever made to her.

I said, “I believe in this idea. I love it. It feels different than other ideas. I am willing to commit to launching this thing whatever it takes, win or lose. But I’m only willing to do that if you are in too. I don’t want you to go along with it just to make me happy and then later regret it. I don’t want you to use it against me later if doing this means we have to suffer. I can’t promise you anything. We might end up living in my mom’s basement. I might be working all night. I might be emotionally drained all the time. We might get clobbered in the market. We might have haters. We might succeed and get rich and have a lot of friends and family resent us for it. I have no idea. All I know is that I’m willing to go for it and live with the consequences, but only if you are too. Take all the time you need to decide if you’re all in. I won’t mention it again. Think really realistically about what it might mean, and whether you will be bitter down the road if it’s tough. If you say no, I will not pursue it.” And I meant it.

She said nothing but, “OK, I’ll think about it.”

I was chomping at the bit. I could not wait to get started, but I also prepared myself for the possible pain of her saying no. There’s only one thing in the world that could keep me from launching this thing, and that was my family. That’s the one thing I couldn’t force and cajole. It had to be real, genuine agreement.

I waited.

I waited some more.

OK, now it’s just getting ridiculous. Did she forget? Is she trying to torture me? Is she waiting for me to sweeten the deal somehow? Maybe I should remind her? No. I told her to take as long as she needed and I told her I’d say nothing more.

So I waited.

We usually make decisions very fast. A few minutes is normal. A few hours an exception. Days? Never.

Two weeks. The longest two weeks of my life.

After two weeks of silence, one day as I was grabbing a snack and she was standing in the kitchen she looked up and said, “OK. Let’s do this. I’m ready.”

That was one of the best moments of our marriage. Probably because it’s one of the few times where I didn’t do any talking. I knew she meant it. I knew it was her saying yes to Praxis, not her saying yes to me. That meant everything. I needed her on my side to go full throttle. She gave me a blank check to pursue this thing come what may. That was by far the most valuable investment in the company. She was the first investor. The first person to believe in the idea so strongly they were willing to put tremendous personal resources at risk to make it a reality.

We’ve had hellish moments. Many. She’s never once held it against me or asked me to stop or complained that Praxis takes a toll. She gave me the go-ahead to keep shooting the ball, even if I went 0-30.

If I had partially pursued it while hoping to win her over just enough to let me pursue it a little more I would have gotten crushed by the first big setback. I could always use the excuse, “Well, I guess I have to stop for my wife’s sake.” Destroying any excuse to retreat or any way to pin it on someone else put me in a position of win or die. Best thing I could have done.

“The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest” — Albert Einstein (unverified)

Ever heard that riddle about whether you should take a million dollars or a penny, doubled each day for a month? Take the penny. You’ll end up with $1.3M if it’s a 28-day month, and as much as $10.7M if it’s a 31-day month.

Doubling is extreme, but even growth of a fraction of a percent compounded every single day can achieve mind-boggling results. When you’re trying to go from idea to inception, progress each day is crucial. You can’t get stuck waiting for one big leap. You need to take at least one step every single day.

Lesson 4: Do one thing every day to make your company more valuable

I was in way over my head when I decided to make the idea for Praxis a reality. How to file for incorporation? Do I need to do that before I build a website? How to build a website? Do I need money? Where to get it? Do I get businesses lined up first, or start selling customers first? What price-point makes the most sense? How to describe the company? Do I need brochures? Do I need a formal business plan? Do I need to build the curriculum first, or get some market interest first? Do I need to setup a business bank account? Who could help me navigate all this?

My brother, a seasoned entrepreneur already, told me to chill out. He said none of that matters right now. “Just do one thing to take the idea closer to reality. Just one thing. Then after that do one more thing. If you run out of things and hit a wall that requires some kind of outside assistance, get it. Until then, don’t worry about it.”

I was mentally trying to solve problems from the future. I had a list of hurdles I imagined stopping me tomorrow, and it was crippling my today.

His advice was freeing. I was still working full-time and wasn’t able to devote all my time to Praxis anyway, so I made a commitment. I would do at least one thing every single day to make the company more valuable. That’s it. Just one thing. No other deadlines or goals of having this or that done by this or that date. Just every day, I had to answer ‘yes’ to the question, “Is Praxis more valuable now than it was yesterday?”

Some days I couldn’t do anything but search the web for ten minutes looking for similar programs in the market, or buying a domain. Not massively valuable, but one thing done.

Other days I spent hours on end feverishly writing marketing copy, contacting business owners, talking with college students about whether they’d consider alternatives, building spreadsheets to play with the business model, talking with web designers, outlining the curriculum content, and more.

I did as much as I could whenever possible, but what really mattered was hitting my minimum of one thing done. What really mattered was not letting a single day go by where this thing didn’t make progress. Time is the enemy with a startup. A day without action means you’re going backwards, losing value.

This approach worked wonders. The idea never lost momentum. There wasn’t enough time to talk myself out of it. Some days I was on fire with enthusiasm and faith in the idea, other days I did my one thing with little excitement and lots of doubt. But I committed to doing one thing every day, so I had to act regardless of inspiration. It moved me from the vulnerable sand of emotion to the unsexy concrete of action.

And it did compound. I made it so much farther than I ever imagined before I even needed to think about things like raising money or addressing big huge hurdles I imagined.

“Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by this some have entertained angels without knowing it.” — Hebrews 13:2

I had a lot to do, much of it outside my ability, much of it costly, and I had a few grand I could put on my personal credit card and that was it. The idea for Praxis wasn’t fundable yet, and I didn’t even know what the letters “VC” meant anyway, let alone how to go raise.

But I didn’t need any of that, because I had something far more valuable. I had dozens of accounts with positive balances of social capital, and it was time to cash them in.

Lesson 5: Social is the most valuable kind of capital

The first decade of my “professional” life was full of meaningful connections. I went out of my way to meet people, follow up with people, respond same-day to every email, look for excuses to write thank you notes (physical ones!), generously offer help without asking anything in return, and connect people to each other whenever possible.

Part of this is my personality. I’m a connector and a people person. But part of it was a choice and it took a lot of practice. I am not sentimental, I move on to the next thing quickly, and I’m forgetful. That made the practice of writing thank you notes the furthest thing from natural. A leader I respected wrote me a thank you note for something small. I asked him why, and he passed on advice someone had given to him, “Look for excuses to write thank you notes.” It stuck with me. I bought a stack and carried them with me everywhere, stamps and envelopes too. I used them generously.

It’s not so much about thank you notes specifically, but the mindset necessary to write lots of them. It requires/develops an abundance mindset. You begin to see win-wins everywhere. You become more grateful and happy. You begin to see subtle ways people just doing their job is helpful to you. This in turn makes you more able and willing to help more people out.

Instead of a social spender, you become an investor in your network. When you meet new people, instead of handing them a business card and asking them to help you, you default to genuine interest in them, a real connection, and seeking any way in which their interests could be served by something or someone you know. Every person you meet has an invisible account with your name on it. Every interaction is a deposit or a withdrawal.

I made deposits. Tons of them. For years and years with no clear payoff at the end. I enjoyed it and it seemed like a good idea. I didn’t have a clear and compelling reason to spend any social capital, so why not keep investing and saving unless and until I did?

When I went all-in on Praxis, I knew this was the time to empty my accounts and even go into social capital debt.

I turned to friends, colleagues, acquaintances, and acquaintances of acquaintances. I cashed in every ounce of social capital I had and got some lines of credit. I asked for introductions, advice, lists of leads, design help, tech help, legal help, strategic help, research help, product development help, and most of all help spreading the word. I traded some phantom stock and paid some cash, but I mostly traded on goodwill and positive social capital I’d built from helping lots of people, being kind and open appreciative, and having a reputation as a guy who helps lots of people.

Had I seen my professional life as a zero-sum game, where I must exploit and best every threat and carve the biggest slice of a fixed pie, Praxis never would have left the launchpad. The fact that I chose to see it as a positive-sum game, where helping as many people win as possible would grow the size of the pie, meant that I had access to a lot more of it when the time came.

The social capital I cashed in to get started was priceless. I’m not being cute. There is no amount of money I could have raised that could have accomplished what a deep, wide, and rich social network did.

I’m so glad I had the patience and self-control to not get spendy early in my career and trade tiny bits of social capital for tiny promotions, pay raises, or prestige. I needed a huge balance to build a company, and my long-cultivated habit of generously depositing social capital everywhere possible was the only way.

“The brick walls are there to stop the people who don’t want it badly enough.” – Randy Pausch

There’s a fatal flaw in your plan. Your business model, or market, or pricing, or something about your crazy idea is going to stop you dead in your tracks. Of course. That’s probably why no one else has done it yet.

Or maybe that’s why you’re going to succeed where they failed.

Lesson 6: Obstacles are for others

I was thrilled. Things were really happening!

Every day, Praxis got closer to public launch. The curriculum modules were under construction, a designer was working on the logo, website, and collateral. I was writing website copy, building relationships with business partners, and building a list of students, events, blogs, and other outlets to push at launch.

Then I revisited my brilliant business model for some tweaks, stumbled upon a paragraph hidden on the Department of Labor website, and damn-near lost it.

My goal from day one was a program that took one year or less and cost $0 to participants who got accepted. They would get awesome coaching, community, and curriculum resources and experience as a startup apprentice, and get hired right out of the program. No debt, no lost time, no boring BS make-work or memorization.

Business partners would get highly vetted raw talent to work and learn under them. They took a chance on younger, less experienced people, but on the flipside they got low-cost talent with great attitude, upside, and ongoing support and training from Praxis.

It was a win-win-win.

My model was simple. The program was free to participants and the apprenticeship was unpaid. Business partners would pay Praxis to find, filter, train, match, and support the participants through the apprenticeship.

Everything I had built so far was around this simple structure. I’d written tons of different copy for FAQ’s, social media, blogs, and the Praxis website and program guides. It was all focused on a zero cost program.

Then I ran smack into the heinous outcome of idiot bureaucrats and corrupt special interests. Public Choice Theory predicts and explains just this kind of thing perfectly.

My model was maybe sorta kinda illegal.

Like most government policies, this one was full of weird exemptions, and impossible to determine with certainty whether I’d run afoul of the law, but it didn’t look good. In typically absurd fashion, a young person could only work for free if they created no value for the company. In fact, the DOL policy read,

The employer…derives no immediate advantage from the activities of the intern and on occasion its operations may actually be impeded.

Yes. Imagine that great pitch to a growing company. “Hey, I’ll provide you an apprentice, but I promise they will not help your business at all, and they may actually impede your progress. Whaddaya say?”

Like all comfy sounding labor laws, this was created at the behest of older, better off workers as a deliberate attempt to shut out younger, lower skilled workers. Vested interests don’t like free market competition.

I was irate and felt defeated by Leviathan. I’ve got no love for government intervention already, so the economist and political philosopher in me spent plenty of energy being incensed.

To think, millions of young people are goaded and pressured into going five figures in debt and staying out of the market for half a decade in college, where they learn near nothing and it’s considered normal. Yet if one of these young people says, “Screw that. I’ll spend no money and go learn by offering to work for free under someone who’s already doing what I want to do!” Illegal. Because, of course, being trained for free is exploitation, while paying fifty grand to learn nothing is education.

I called my brother. I told him they did it. They killed my dream with the dead hand of policy. I was despondent. I began to realize that I had been naive all along. Of course there’s some big obvious reason no one else is doing this. C’mon Isaac, you really think you’re that special? That no one else had an idea like this?

My brother laughed.

At a time like this, he laughed.

I said, “How is this funny?!” He said, “Look, there’s always some obstacle like this. That’s what keeps away everyone who doesn’t want it as bad as you. Stop getting mad and get creative. There’s always a way around it. Don’t give up. Find it.”

That’s it. He was utterly unconcerned. To him, it was a given that I could navigate around this law. He seemed to think it’d be fun. That change of mindset changed everything. I smiled and realized he was right. This was going to be one more reason I would succeed, because it’d be easy to stop now, and I wouldn’t.

Something amazing happened almost immediately after I switched my mind from helpless victim of state oppression to clever entrepreneur excited by a challenge. I found a way around it. It was actually rather easy and obvious, but I was too blinded by anger and defeat to see it at first.

Participants would pay tuition. Then they’d get paid by the business during their apprenticeship. What they earned would equal or exceed what they paid. The end result (though a little less sexy marketing-wise) was the same. Participants got all the same benefits and an apprenticeship in less than a year for $0. Praxis earned the same revenue, and business partners paid the same for talent.

I felt dumb for missing such a simple fix. But I can’t overstate the extent to which I thought my dream was dead. Mindset is everything. If you’re willing to take no for an answer, you’ll get it. If you’re not, you’ll navigate a sea of no’s until you find a yes.

“Maybe I destroyed the game. Or maybe you’re just making excuses.” — Michael Jordan

They can do it because they got funding. You’re stuck because you need money to do all the big things necessary to grow your startup idea into a real company. If only you had the advantages they do! Of course they have traction, because some VC took a chance on them. You can’t get customers without money!

Lies.

All lies. I had to learn and relearn this. I thought I needed money. Nope, not yet. Maybe now? Nope. Still more I can do. Now? Still no.

Lesson 7: Don’t look for money until you’ve tapped out everything else

It takes a lot longer to exhaust all possible bootstrap growth activities than you think. When money is not an option, you get way, way more creative. Every time you think you’ve reach a true stopping point, where nothing more can be done without money, you discover a new batch of things you can do to move forward.

I’m not for or against raising money. What I’m against is closing off your greatest asset – your work ethic and imagination – because you’ve bought the, “I can only do X with money” narrative. I’m wary of this narrative because I had to fight it. It’s a tough opponent.

My brother bootstrapped a company for seven years with no outside funding. When he went to throw gas on an already growing fire, he was able to raise $10.2M in less than a year on great terms. It was his sound advice that tied me to the mast to resist the Siren song of fast funding.

I’m good at selling a vision. Raising money seemed an easier task than grinding out some traction. I kept thinking I’d better go raise so I could build the product the way I really wanted to, market the way I really wanted to, etc. My brother’s advice reeled me back in.

I’ll never forget it. We were sitting in my 2002 Saturn in an Isle of Palms parking lot outside a hotel where he was spending the weekend while visiting us. He said, “What are you stressed about? You have an ideal situation. You have a great job that allows you to build this thing on the side for the time being. Just keep doing that. Do every single thing you can before you even worry about the need to quit your job, raise money, etc. Not only will everything you do now improve terms for any future funding, but if you had a million dollars right now, how would you use it? You’d probably waste it. You can try stuff cheap now, experiment at low risk, and figure out what efforts are worth more money.”

I knew he was right. I didn’t want him to be right, because the, “Imagine all we could do with money” narrative is exciting and intoxicating. But I knew I could do a lot more before I actually ran into walls that couldn’t be climbed without money. I also knew he was right about wasting it. If I had a million dollars to start Praxis, I shudder now to think of all the ways I would have misused it. I needed small victories under my belt before I took any big swings.

Not only does bootstrapping as long as possible mean you get more creative, figure out what gets traction, and improve future terms, it also means you have more skin in the game. This is an important incentive structure. The more you are playing with your own resources, the sharper your decisions. Milton Friedman famously described the four ways to spend money, and the level of care with which you’ll act in each case. You’re the most prudential spending your own money on yourself, less spending your own money on someone else, less spending someone else’s money on yourself, and least of all spending someone else’s money on someone else. The longer you can incentivize the wisest form of spending, the better.

Outside funding isn’t evil. It’s wonderful and can be necessary. I ended up raising an Angel investment just nine months after deciding to build the company. Paradoxically, it was only after I firmly committed to build the company without funding that people began to take notice. I didn’t seek the Angel investor, he sought me. Why? Because I had a bit of buzz and traction. Buzz and traction I wouldn’t have if I’d spent those months chasing funding instead of trying to get my first customer. I was building the company, with or without money, which made the prospect of investing attractive. People want to invest in momentum, not just ideas. I wasn’t bluffing. Praxis was going to keep moving, money or not. That commitment was necessary.

Every time I thought I was out of steps and needed money, I refused to let myself give in to the narrative that money was my only move. I’d ask myself, “If money wasn’t an option and would never be an option, what would I do?” There was always something.

Maybe well-funded startups destroyed the game. Or maybe you’re just making excuses.

“Everything I do, I do it for you.” – Bryan Adams

You’ve got a dynamite idea and a great product. There are so many angles to market it, and so many verticals to sell. You see a future where your customer base is massive, and you don’t want to exclude anyone in your early efforts. You struggle to define your target market, because you want it so big. You struggle to define your pitch, because it can alleviate so many pain points for different people.

I feel you. But if your market includes everyone, it includes no one. I knew I’d do better with a tighter market. Ideally, as Peter Thiel describes in Zero to One, a tiny niche I could monopolize.

But even this was broad enough for me to lose focus. The real break-through for choosing actions to get traction came when I got down to the smallest unit possible.

Lesson 8: Focus on a single customer

No company serves “society”, or, “consumers”, or, “Millennials”. These aggregate abstractions are useful in a pitch deck to describe the macro landscape, but when the rubber meets the road, a company can only serve real, individual human beings.

When I was bootstrapping Praxis and trying to exploit every low-cost marketing and PR opportunity possible, I realized the message was only potent when highly targeted. “Hey, ambitious young people, check this out!” is pretty weak compared to, “Hey Jane Doe, let me show you how this can help you achieve your specific goals.”

Whether targeting Jane Doe is scalable doesn’t matter. Common (and very good) advice about startups is to do things that don’t scale at first. Worry about scale after you have traction. But I think a target market of one is more scalable than it seems.

In marketing, it’s sometimes called a customer Persona or Avatar. You create a fictional person with a background and bio, and you tailor your message and medium to them. It’s often more effective than tailoring it to a big lump like, “18-25 year olds interested in business and entrepreneurship.” When you market to a collective, it feels that way to your market. No one likes to feel like an interchangeable member of a homogeneous blob.

I didn’t know the marketing mumbo-jumbo or research it. I just realized that a thousand fans or ten potential customers were worth nothing compared to one actual, paying customer. Especially when doing something totally new, where social proof is key.

I created a hypothetical customer in my head. I asked myself, “What kind of person would love Praxis, and what kind of person would Praxis love?” I defined this person in detail.

I pictured a guy who had a few semesters of college he paid for himself and hated it. He’d attend a specific conference where I was speaking, and have specific intellectual interests and life experiences. I wanted a raging individualist from the Midwest who mixes practical, not-to-good for anything work ethic with wild Silicon Valley dreaming and lots of swagger. When I wrote and spoke about Praxis, I spoke to that person directly. It was a certain type of individual within a small niche of young people I already knew well.

Then I met him.

I was speaking at a conference in Michigan when a guy came up to me brimming with confidence and restlessness and asked several direct questions about Praxis. I decided then and there this would be my first customer. I didn’t care about anything as much as getting him into the program. He was the customer I needed to prove the model. If it couldn’t work for him, it was doomed anyway. If it could, it opened up the possibility of so many more customers in so many more niches.

He started his application on the spot. But it took several weeks and lots of emails and calls before he decided to make the leap, quit his job, drop his schooling for good, move away from loved ones, and go all-in. His name was Mitchell Broderick, and he turned out to be a smashing success story that has helped pave the way for many more customers. He proved what’s possible for a Praxis participant.

I never would have sold Mitch had I tried to sell his entire demographic. I never have sold him had I tried to do it in a scalable way. My choice to channel all my efforts to one specific, imagined customer led me to one specific, real customer for whom I targeted everything.

Lots of people will tell you they like your company or would buy your product. This means absolutely nothing until you get one to pay for it. Forget about tweaking and optimizing your approach to fit some conglomerate of opinion from people with no skin in the game. Instead, define down to the last detail your ideal first customer. Target one single person, real or imagined, until you make a sale. Get someone to pay you. Only then is your idea real, and market-proven.

Then do it again. Then again.

“I sold some stuff.” – Lloyd Christmas

Alright, the company is real now. But your product requires some resources that only come when you have commitments from customers…and customers require a product before they’ll commit to anything.

It might be time to sell something you don’t yet have so you can get the resources necessary to build it.

Lesson 9: Sell stone soup

There’s a children’s story about three hungry soldiers who wander into a small village. They go around asking for food, but the villagers say they don’t have any to spare. Undaunted, the soldiers decide to capture the imagination of the villagers. They announce they will make stone soup.

Everyone’s curious. They bring a pot and water and some stones. As it begins to boil, the soldiers describe how delicious stone soup is, and how they’ve made it for very important people. The villagers are excited to see how they can possibly make soup from stones. The soldiers comment that it’d be better with a few carrots, and an excited villager brings them some. Same for potatoes, barley, cream, meat…you get the idea. Soon the whole village has a great feast with soup, bread, beer, and dancing. Everyone loves it. All from three stones!

The take-away from the story me helped get Praxis off the ground.

The soldiers knew if they had the resources, they could feed themselves and deliver an end product the entire village would love. Just asking for ingredients wouldn’t do. They had to sell the end product before they were capable of delivering it. They needed to paint a picture of the possible as if it already existed. They took a gamble on themselves. They knew if they could sell the vision, they’d be able to deliver in the end. Had they produced a bad soup, or kept it all for themselves, they’d be run out of town on a rail.

Whether a pre-sale, KickStarter campaign, or straight-up commitment to deliver what you don’t yet have, some early stage businesses needs to solve the customer-product catch-22.

I needed good businesses who would host apprentices. I needed good apprentices who would create value for businesses. I had to sell stone soup.

I went to my personal network of business owners, and asked them to introduce me to other business owners, and presented a theoretical proposition: If we had great young people who were highly vetted and trained by Praxis, would you host them in your company for a paid apprenticeship? I described the customers I hoped to attract, even though I didn’t yet have them. I got about 20-30 businesses to say, “Yeah, probably.” Good enough. Those were our first business partners.

I listed them on the website and used them as examples of the BP’s in our network when recruiting applicants. I knew if I had good people, I could place them at these and other businesses, even though no company had given me a firm commitment to host.

We got applications and accepted our first 6 participants into the first class of the program. Now the real work began of delivering on the promise. Participants in hand, I went back to the theoretical business partners and made it real. “Take a look at this person. You up for bringing them on as an apprentice? We’ll provide X, Y, and Z, and you just need to provide a great experience with Z, B, and C.” It took a lot of shopping to find the right fit. But I did, and now we were real. We had real business partners and real customers.

The business partner network today is dramatically different than it was then. In fact, of those first 20-30 BP’s, probably only 4-5 of them even meet our criteria anymore. We got a lot tighter, more clear, and more demanding in what we expect. With a track record of quality talent, we can afford to. Now when we say we have businesses in nearly every major city, we have actual businesses who have explicitly agreed to host apprentices or are doing so now. When we started, we just had belief in the ability to make it happen.

Selling stone soup is scary. If you can get all the resources and build the full product before selling, do. But often you can’t, and you have to decide if you’re going to let it stop you, or if you’re going to bet on your ability to deliver and sell a product that doesn’t yet exist.

“It ain’t about how hard you hit, it’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward.” – Rocky Balboa

When your company is a newborn, all you can think about is throwing that knock-out uppercut on the status quo. You’re here to disrupt. You’re here to claim the belt. You’re here to posterize the stale old industry with a down-for-the-count sledgehammer.

You’re one punch away from hoisting the heavyweight title.

Problem is, you don’t have enough time to throw that big punch because you’re taking jab after jab after jab before you can gather yourself.

That’s when you realize that staying on your feet to go the distance might be more important than that one big blow.

Lesson 10: Taking a beating beats throwing the big punch

About a year in to Praxis we started to get pounded. The excitement of launch faded, so too the excitement of getting the first customers, launching the first class, and seeing them graduate with success. The big firsts were over. Now we had to do it all again, but more, bigger, and better. And we had to generate our own buzz because we weren’t inherently cool for being brand new anymore.

Not only that, there were all kinds of problems revealing themselves. Our application process was in need of improvement. Our business partner on-boarding process too. Our website was getting stale. Our spreadsheet “CRM” was pushed to capacity. We had no real marketing funnel, and though we produced tons of excellent content, we weren’t effectively using it to capture leads. We knew how to broadcast our message, but not to connect and engage those intrigued by it.

It got worse. We had a few bad experiences with participants flaking at their business partners, burning bridges and costing us revenue. Year two growth was slowing. Then the worst of all imaginable things happened. We lost one of our participants. Nothing grinds you to a halt like the death of someone close to you. Nothing.

I was overwhelmed. It felt like a flurry of punches from nowhere.

On the long car ride home from a Future Business Leaders of America conference in Nashville, I turned on one of my favorite podcasts, EconTalk, to hear a conversation between host Russ Roberts and WSJ’s Gregory Zuckerman about the energy boom in the middle United States.

One of the things that struck me from the stories of wildly successful oil and natural gas “frackers” and investors was how often, how big, and how long they failed. The ones who succeeded in the end owed (at least) as much to persistence and outlasting the competition as they did to special insight or entrepreneurial genius.

Some of these people just kept taking failures the way Rocky took head-shots and body blows, and staggered back up to attempt another wild punch. At times it seems almost sad. Rocky evoked pity in round after round, face bloodied. Yet he became a champion.

What made him great was not his powerful knockout punches, quick footwork, graceful dodges, or lightning jabs. What made Rocky great was his ridiculous ability to absorb punch after grueling punch, in body and in spirit. He just kept getting back up. At some point, the punches slowed a bit and his opponent ran out of steam or made a mistake.

The more I studied entrepreneurs, the more I realized the big closers or lucky long-shots are the rarest of exceptions. The real winners are the persistent ones, not necessarily those with the best ideas, salesmanship, funding, or operations. All these things matter. A lot. Yet no matter how good you are at them, you are going to take some big hits.

At all stages in the process, major disappointment or surprise will blindside you like a mouthguard-flinging left hook. Not just one at a time. Several in succession. And just when you think you’ve steadied yourself, one more. The great ones keep going. They take the hits and fight on.

I felt like crap. But I realized something. We were still standing. We were still standing. We weathered the shitstorm, and we weren’t done yet. Every day that we kept going increased the odds that’d we’d pull out a win. I started whispering to myself regularly, “Just keep standing. Just keep standing.”

We did. We made it through a really, really rough six months or so. It felt like an eternity. We made changes to every aspect of the business. Things began to pick up, and we started to land more punches than we took. A year later, we hit an incredible groove and started stacking wins fast (followed, of course, but another series of gut-busters).

I take tremendous pride in our resilience. A lot of teams can rock it when the world’s complying. Few can stay glued when the haymakers come.

Others advise that big hits are the market’s way of telling you to throw the towel before you drop for good at the hands of an unstoppable force, Apollo Creed style. But I don’t think most of us are in danger of staying in the ring too long, and in this country, it’s pretty hard to hit unrecoverable rock-bottom as an entrepreneur. I say stand.

For me the lesson on that long car ride was simple and uplifting: When it comes to long-term success, it’s more important to take punches than to throw the big one.

Someone else can always hit bigger than your best. Not many can survive the full twelve rounds.

“There is no silver bullet that’s going to fix that. No, we are going to have to use a lot of lead bullets.” – Bill Turpin (quoted by Ben Horowitz)

There’s always that one hurdle that won’t give. It’s the bottleneck slowing growth. There’s got to be some big, clever tactic that vaults you over in one swift motion.

You start banging your head against the wall, hoping to have a eureka moment that solves it. I did. Then I picked up The Hard Thing About Hard Things by Ben Horowitz and confirmed a depressing, freeing suspicion.

You probably won’t find a silver bullet. You probably have to destroy that hurdle with thousands of lead bullets.

Lesson 11: Stop looking for a silver bullet and start spraying lead

In the first year of Praxis, there were several desperate-for-a-silver-bullet moments. Bewildering circumstances where the gum in the works couldn’t be pinpointed. Just a tough slog. Every step forward took Herculean effort.

This can’t continue if we’re going to grow like we want to!

The temptation to find a silver bullet crept in. I’d lay awake at night wonder what the one breakthrough was that would free us from the relentless grind. I’d fantasize about a big PR hit out of nowhere, a new vertical that would sell itself, an investment that would magically grow everything, or a new employee who had all the secrets.

Silver bullets are rare, and probably can’t be found on purpose. For me, even the desire for one was (and is) dangerous.

The desire for a silver bullet shifts energy and attention away from what’s in my control to a series of delightful hypotheticals about what might happen if lightning struck. It slowly dragged me into a passive, victim mindset, away from an ownership, action bias.

This happened many times and I had to fight it every time. Whenever I caught myself saying, “If only we had…” I administered a figurative slap on the wrist.

Consistent firing of lead bullets isn’t glorious. It’s ugly. Even when stuff starts to hit the target, you’ve got so much ballistic material flying everywhere it’s hard to isolate the accurate shots and repeat them.

This is not an argument in favor of wild inefficiency. The more you can narrow it down to the most effective and repeatable tactics, the better. But continuing the salvo is more important early on than putting the action on hold while you try to guess the perfect attack.

Every time I think we’ve finally outgrown the chaotic lead bullet phase and become deadly silver bullet snipers, I’m wrong. There are areas of the business that mature into tighter tactics for sure, but there is always some frontier somewhere with no silver bullet that demands a pistol-packed posse to recklessly drain lead.

A lot of people go down in search of a silver bullet. I decided that wouldn’t be me, and if I went down, I’d go down firing whatever I had, silver or lead.