There is a revolution happening in higher education. It’s happening without fanfare. It’s in what futurist investor Peter Diamandis might call the “deceptive phase”. This revolution is the rediscovery of a longstanding idea that somehow got lost in the last century or so: apprenticeship.

The Loud Nothing

Higher education is a popular target for reformers. For at least a decade there have been protests over student debt, which averages well into five figures per student (six figures is not uncommon). Blame is lobbed everywhere. Tuition has risen faster than any other good – more than 500% in the last few decades – fueled by growing demand fueled by subsidy and government-backed loans fueled by a belief that, without college credentials, everyone will be poor and have fewer career options. Ironically, credential-chasing is making people poorer and limiting their options.

More than half of college grads have no job or a job that does not require a degree. Employers find little to no value in whatever colleges are supposed to be teaching (which comes as a major surprise to grads; take a look at how they think they’re prepared vs. how employers think they aren’t).

Debates rage. Some propose forcing taxpayers to fork over even more money for more college for more people. Some propose caps on tuition, or student debt forgiveness, or new laws requiring employers to pay more. Some propose new subjects, teaching methods, programs, and efforts to cajole young people into majoring in whatever field is the economic fortune teller’s flavor of the month. “We need more STEM!” “We need more critical thinkers!” “We need more….”

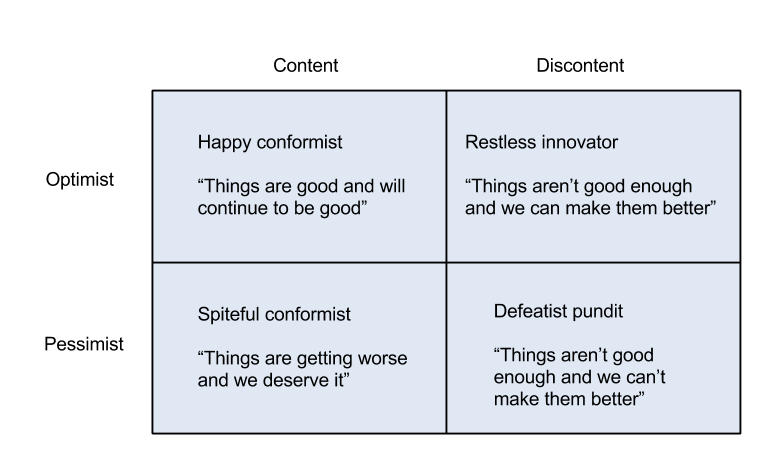

All of these collectivist approaches are fundamentally arrogant and irrelevant, however well-intentioned their advocates. The funny thing is, while pundits wring their hands and raise their voices with clueless frustration, the market is on the move…

The Silent Something

I read a long and thoughtful policy paper the other day (ok, I skimmed it…it was pretty boring) about apprenticeship as a potential solution to problems plaguing higher education. It came to a predictably safe and meaningless conclusion: apprenticeship could be beneficial, but there are complications that must be worked out.

Meanwhile, in the real world where real people have real skin in the real game, apprenticeship is already undermining the old apparatus and freeing people and businesses from the costly credentialist conveyor belt.

It turns out self-interest, entrepreneurial risk-taking, and profit and loss signals are sufficient to induce radical change in a stagnant industry (I guess Adam Smith was onto something). It didn’t take think tanks, wonks, and talking heads putting together a “sound plan” for a “bold future”. It didn’t take ballots or protests. It took individuals pursuing their own dreams, bucking peer pressure and the status quo of religious devotion to debt-fuelled four-year binge drinking and test-taking. Innovation beats politics.

I’m speaking from personal experience. I’m one of these individuals and my skin is in this game. I staked everything on the value to young people of gaining great apprenticeships and becoming entrepreneurial creators outside of the classroom when I launched Praxis. I’m not talking theoretically, I’m seeing these young revolutionaries do it every day.

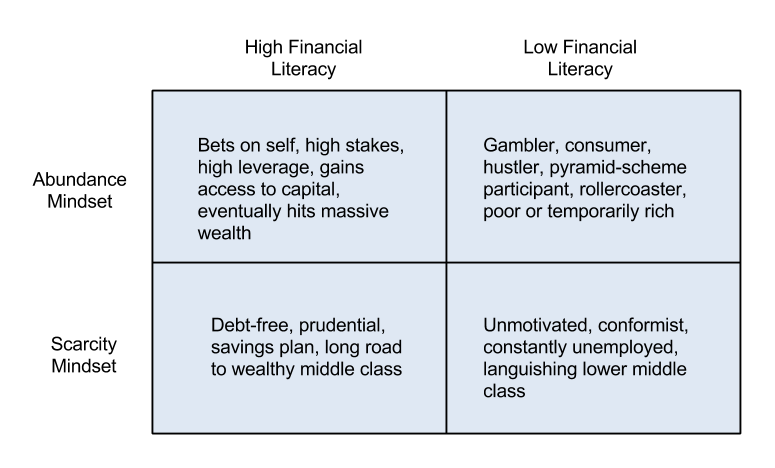

This revolution isn’t anything that needs to be designed by planners, or gain consensus. It’s not a revolution for “society” or other abstract collectives. It’s an individual revolution. One by one, the best and brightest are opting out of classrooms and breaking down the wall between learning and doing. They’re apprenticing at real businesses, creating real value, and gaining the skills, knowledge, network, experience, and confidence needed to succeed in less than a year for zero cost.

The New Apprentice

What kinds of individuals are leading the apprentice revolution?

Apprenticeship isn’t just for welders, and startups aren’t just for coders. The apprentice revolution is driven largely by eager, hard-working generalists. Young people who don’t yet have a specialized skill set or specific life plan. They want to create value and they know they won’t find a perfect career without testing a lot of things. They’re doing things like sales, marketing, customer service, product development, and an array of activities too varied to be labelled. They’re doing this primarily at startups and growing small businesses – places that need talent, but can’t afford a cubicle farm of coffee-fetching interns. They see the unique benefits of an apprenticeship vs. the standard approach.

It’s easier than ever to start and grow a business. Talent is the biggest constraint faced by every growing company. College credentials are not only killing the classroom, they’re losing all of their signalling power to employers. Today, young people must find a better way to signal their ability to create value. The best companies are looking for the best talent based on what they can do and prove, not lifeless bullets on a resume. They’re turning to apprenticeship.

A Way of Life

The apprentice revolution is not just a better way to learn and work. It’s a better way to think and live. It’s deeply rooted in a philosophy of personal autonomy, growth, and innovation. It’s about freedom, not just in theory or legal code, but in each person’s daily life. It’s built around the idea of free exchange and value creation, not obedience and entitlement.

Rather than the passive, rule-following mindset bred by an education system isolated from the dynamic market, the apprentice approach is fully immersed in commerce and requires creativity and insight to meet the needs of others.

A free and prosperous society emerges from the actions of free and prosperous individuals, not slavish students of arbitrary facts. It emerges when we’re not looking, and in ways the intelligentsia don’t expect. The revolution in higher education is already here. It’s not on the evening news. Instead, it’s quietly creating the products and services you’ll be buying tomorrow.

Forget politics. The real rebels and revolutionaries are building the world without anyone’s permission. Apprenticeship is but one example in one area. Opportunity abounds.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

Like this:

Like Loading...