I love a good two by two matrix. Trying on new lenses through which to interpret the world is a big part of intellectual exploration. Plus, it’s fun. I have been fascinated for some time with differences between generations, especially since I’ve interacted a lot with Millenials (or Generation Y) in the last several years, and now I’m interacting with the next generation (I’m calling them Generation Z, because I’m not sure any other title exists currently). There are some pretty significant differences between these two generations, not to mention the huge difference between both and Generation X, Baby Boomers, and even earlier generations.

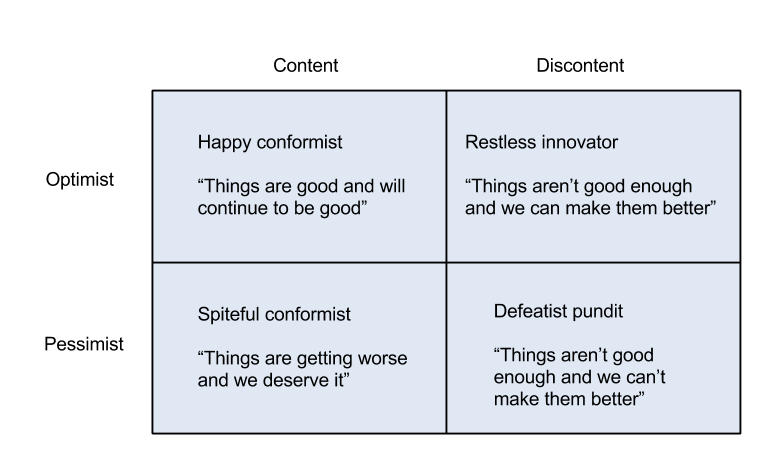

In order to explore these generational differences, and to sate my desire for matrices, I put together the Obedience-Entitlement matrix. Obedience – the degree to which a person follows orders and maintains existing norms – is measured from high to low on the vertical axis. Entitlement – the degree to which a person believes they are owed something from others – is measured from high to low on the horizontal axis.

You can see the four quadrants that result. The first label in each quadrant describes the dominant trait displayed by individuals or groups in that quadrant. The second label in each quadrant serves as a kind of archetype, describing informally the role people in that quadrant play in a society. Don’t mistake the second label as a career description. It may be that, but obviously many societies don’t have slaves in the formal sense, and many people who make good soldiers are not necessarily soldiers, etc. You get the idea.

Don’t be too distracted by the word “Slave” in the upper left quadrant. Again, it’s an archetype. I tried to think of a less loaded but still accurate word to describe people who are highly obedient and don’t challenge authority, and are highly dependent and expect to be taken care of. Slave is the best word I could find. Obviously not the kind of slaves that revolt or escape, but kind that accept their lot and seek nothing more than the most comfortable slave life possible.

So here’s where I started having fun with it. Thinking in terms of generational differences, I tried to map out the dominant characteristic that describes each of the last four generations. The Greatest Generation and Boomers were pretty easy. It gets harder after that.

The ‘Greatest Generation’

The WWII generation fits pretty nicely in the upper right quadrant. They tend to be deferential to authority and feel a need for maintaining a constant order in the world. They don’t mind knowing and staying in their “place”, and they don’t expect anything for free. This generation is accustomed to earning everything through hard work and individual effort, and they keep their gripes to themselves rather than upsetting the apple cart with direct action.

Baby Boomers

Boomers are in the bottom left quadrant. They grew up questioning everything and tearing down what didn’t suit them. A big part of their revolt came when they felt they didn’t get what they deserved. They want things, and you’re damn-well gonna give it to them. This is a group that’s willing to question all authority structures, and yet doesn’t mind fawning over those promising free goodies. This is a source of radical idealism, but practical problems.

Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z

Here’s where it gets hard. I’ll theorize on why it gets harder in a minute, but first let’s see what we can do.

Generation X might be the least clear. I consider myself a Gen Xer, even though my date of birth may or may not put me in the tail end of that group, depending who you ask. I have older siblings and grew up primarily with people and accouterments considered Gen X. So what does grunge music and a bunch of movies about discontent corporate workers and long-haired slackers mean for the matrix? I’m still not settled on this one, but I think Gen X is mostly in the upper right quadrant in deed, if not in words. You don’t see the abiding respect for authority that the Greatest Generation displays, yet for all the complaining and philosophizing about the system, Gen Xers pretty much do the ‘normal’ thing. They complain about it and feel like it’s pointless, but they do it. Xers don’t seem to have a strong sense of entitlement either. In fact, they seem to expect mostly bad things to happen, and have made a kind of stoic peace with it.

On to Millennials. Here’s where I’ll tick some people off. If I can narrow down the diverse set of Gen Y characteristics to only the most common, I’d have to place them in the upper left quadrant. Millennials are demanding and ‘high maintenance’ if you ask employers or parents. But not in a revolutionary way that truly scares those in authority. Millennials aren’t threatening to the status quo as much as they are frustrating. It’s hard to know what they need. They want a lot of things, and they want someone else to figure it out and give it to them. They aren’t afraid to openly criticize or make demands of authority, but mostly as a way to vent emotions. They want to be taken care of above all, and have an abiding sense that the world is unfair if they don’t get what they want. If you provide, they’ll obey.

Generation Z is really interesting to me. Only in the last few years have I spent a good deal of time around this generation. I place them primarily in the bottom right quadrant. They’ve seen older siblings pay a lot of money for college only to end up in debt living in the basement. They’ve never known the phenomenon of ever increasing home values and 401(k)’s. They don’t expect their lives to be better than their parents by some automatic function of time passing. They’re not entitled. But they also feel comfortable openly criticizing existing institutions. Unlike most Millennials, however, they’re not afraid to do something about it and pay the price. Unlike boomers, they don’t see revolt or reform as the best way to confront the status quo. They simply walk away, opt out, and exit what they don’t like. They’ve grown up in a world full of options, and they don’t feel the urge to go along with, or revolt against the game. They just quit and find or create a new one.

The End of Generations?

X, Y, and Z are pretty hard to easily categorize. Not just on this matrix, but in general. They don’t seem to share really dominant characteristics the way previous generations do. Perhaps that’s because not enough time has yet passed for us to have the ability to look back at their full record. But I also suspect that the value of defining generations is declining across the board.

We have more choice and customization than ever. It was once the case that everyone in a certain age range was sure to have a lot of shared experiences. You saw the same shows, heard the same songs, wore the same clothes. There weren’t many options. Today it’s not uncommon for one 18 year old to be a huge fan of a band or TV show that another 18 year old in the same town has never even heard of. The number of shared experiences and cultural icons has diminished. This is a very exciting development! Oppression and stagnation thrive off of sameness. Collectivism is a dangerous mindset, but it’s becoming endangered.

Your Turn

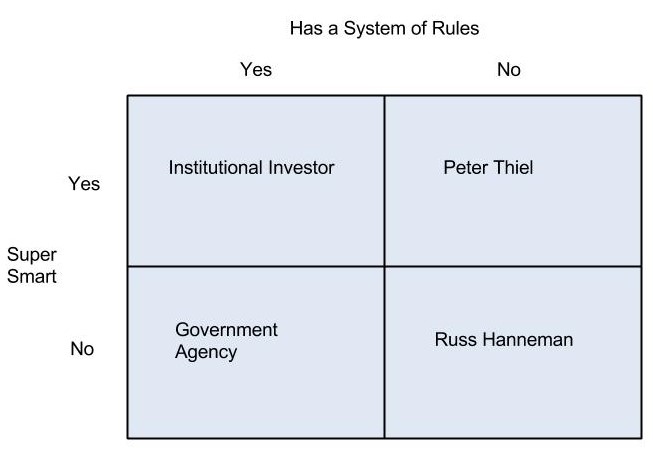

Play around with the matrix yourself. Place generations, individuals, companies, sports teams, or anything else on it. Tell me why I’m wrong. See if you can adapt it to be of more use to you.

Like this:

Like Loading...