About half a dozen years ago, I read two books in succession that I did not expect to have much to do with each other. They both proposed intriguing dichotomies. These dichotomies cut up the world differently, but I began to see interesting ways they could be layered on top of each other.

The books were The Future and Its Enemies, by Virginia Postrel, and A Conflict of Visions, by Thomas Sowell.

Both books are phenomenal and I highly recommend them. Let me briefly describe the central dichotomy presented in each.

Stasists vs. Dynamists

Postrel defines two outlooks on human life and society, static and dynamic.

The stasist fears and resists change. They wish to preserve things as they are, or possibly even return to an imagined glorious past. Every change, whether social, technological, or environmental, is bemoaned as the harbinger of all manner of moral and civil decay.

It’s an obvious mindset to spot in many conservatives, exemplified in William F. Buckley’s mission statement for National Review, to “[S]tand athwart history, yelling Stop”, but it doesn’t just describe conservatives. A great many modern liberals fall into this category as well. Environmentalists who fear invasive species or believe any changes to any ecosystems are always bad, unionists who want to set work arrangements and productions methods in stone, or social justice advocates who wish to maintain certain ratios in material wealth between people.

The dynamist embraces change and does not fear it. This includes fans of free markets, free speech, and economic growth, techno optimists and pioneers. Dynamists are, by nature, less organized but also more prone to have a big impact on the world individually. Again, it cuts through simplistic left/right political paradigms and includes some liberals who want mores to evolve and some conservatives who want industry to do the same.

Constrained vs. Unconstrained

Sowell has a different dichotomy. It’s a bit more subtle, but like Postrel’s, it does not fit into left/right political rhetoric neatly. He defines two visions of the world and humanity, constrained and unconstrained.

Those with a constrained vision see certain physical, moral, or spiritual realities as unchangeable. Scarcity, self-interest, human fallibility, and evil. This doesn’t make the constrained vision a pessimistic one, but simply, to quote the great economist Peter Boettke, “Puts parameters on utopias.” You can improve the world only by first understanding the fundamental laws of both material and human nature. You can’t achieve flight by wishing away gravity or achieve human harmony by wishing away greed. The constrained visionary realizes these parameters and innovates in ways consistent with them. Smith’s Invisible Hand and Hayek’s Spontaneous Order are fundamentally constrained concepts, as they accept human avarice and limits to knowledge and describe social orders that turn all that imperfection into progress.

Those with an unconstrained vision see everything as perfectible. We can eliminate scarcity (this is very different than simply “have an abundance of stuff”, as it assumes time and choice can also be eliminated), we can remake man into a perfect version, we can stop playing by old stuffy rules and simply rebuild a society without greed. If humans are flawed we can remake humans, instead of forming social orders that work around the flaws. We don’t need institutions that channel bad desires to good outcomes, we simply need to remove bad desires.

Both conservatives and liberals alike throughout history have had both visions. Individualists and collectivists are not neatly plotted into one or the other. Jefferson had a more unconstrained vision, along with the French Revolutionaries and many early anarchist and socialist revolutionaries. Modern anarcho-capitalists and Burkean conservatives alike share a constrained vision.

Let’s add them together and see what we get…

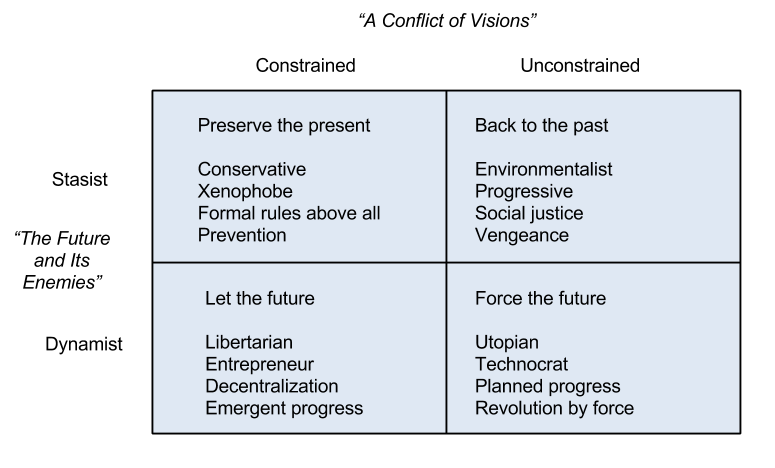

Yay, time for a 2×2 matrix! Don’t take this too seriously. It’s been a while since I read these books and I’m playing around with this ideas rather loosely and humbly, so don’t get caught up on specific verbiage. Instead, see if you can gain anything from the intersection of these two dichotomies.

In each quadrant I include a single phrase that I think defines the dominant desire, then list a few ideologies, groups, and types of action and orientation that I think fit it.

Why now?

I got to thinking a lot about this recently when reading the phenomenal series, Breaking Smart, by Venkatesh Rao. (If you read nothing else this year, read this!)

Rao describes the implications of the fact that ‘software is eating the world’. Part of the analysis involves the inevitable backlash against software-enabled progress and disruption. Rao calls the resistors Pastoralists, and provides a very compelling look at the two apparently opposite ways pastoralism manifests.

One is a resistance to all change. The other is driven by agents of change themselves who adopt a single vision of change and wish to force it on the rest. You can see how the first might fit into Postrel’s stasist category, but the second doesn’t quite. That’s where combining Postrel and Sowell becomes so powerful.

I think the three great threats to human freedom and flourishing today are constrained stasists (resist all change), unconstrained stasists (remake the world in the image of the imagined past), and unconstrained dynamists (force the right kind of progress on all these hapless idiots).

I think all the promise and joy comes from the outlook of constrained dynamism. One that understands failings in human knowledge and virtue and the physical reality of scarcity and wishes to allow change to emerge and evolve organically within unplanned orders to address them in ways no one can imagine ahead of time.

See if you can map yourself or others on the matrix!

You can also check out other fun 2×2 matrices I’ve played around with on various topics: